You're exploited. It's okay to hate work

JW Mason's criticism of Joan Williams fetishizes unjust labor.

It seems to be a professional obligation among online pundits and academics to periodically accuse Jacobin of racism; at the very least, it’s a good way to whip up positive engagement from anti-socialist liberals. This line from econ professor JW Mason, however, is particularly flimsy even as far as these things go. Even if you read this, as he does, as “poor people are lazy” — isn’t this a classic (perhaps the classic) anti-poor trope? Mason suggests that this is a Charles Murray dogwhistle about how lazy BIPOC are, but it’s odd to accuse Williams of subtext when the text itself is explicit. I suppose he knows his audience: if you love Jacobin-punching, you probably don’t care all that much about classism anyway.

That said, if you read the interview not looking for a gotcha, you’ll notice that Williams does not actually say that the poor are lazy. Neither does she say that they are incapable of self-discipline. What Williams is talking about is the way that “the values of the rich and the poor differ from those of the workaday middle,” which, she argues, helps to explain the middle class’s support for Trump. Her specific argument is that what the poor value — not, that is, how hard they work or are capable of working — helps explain their partisan preferences.

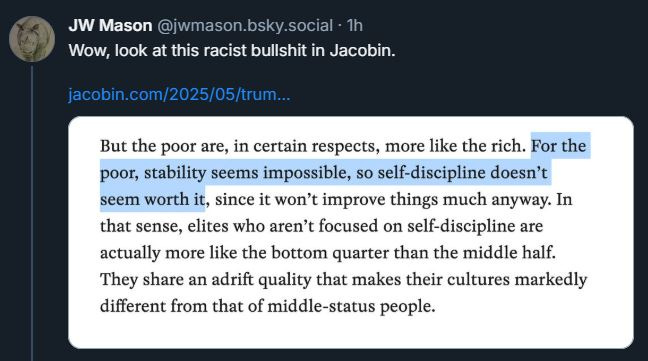

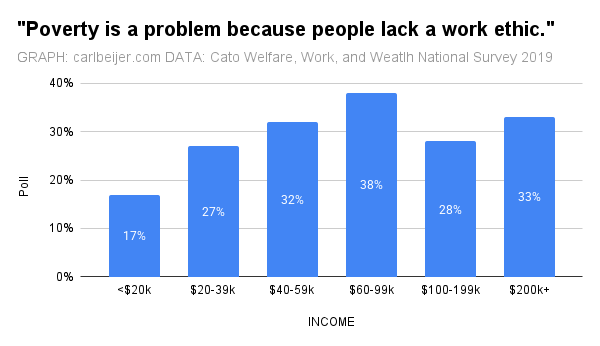

As a matter of empirical fact her point is uncontroversial. Here’s a typical poll:

It’s just demonstrably true that poor people do not romanticize work in the same way that the middle class does. They are less likely to see it as inherently virtuous or demonstrative of one’s ultimate worth. The sociological reasons for this are obvious and well understood. As Weber famously argued, the unusually robust valorization of work in Western Europe and the United States reflects more than anything the cultural ascendancy of reactionary Calvinist ideas about success. It also, of course, reflects the way capitalism centers our personal value around our usefulness to the ruling class. So we are taught for example about “the dignity of labor” and implicitly taught to view the unemployed as lacking dignity.

This is far from a universal perspective or an expression of some intrinsic “human nature” love of work. During my time in former Soviet states for example I am always struck by how older residents in particular often have little affection or reverence for their jobs. There is honestly something refreshing and affirming about walking into a local convenience store and doing business with a cashier who would much rather be watching soccer — which you know, because he is actually watching a televised game on the clock. As Barbara Ehrenreich observed in her excellent Smile or Die, one of the most inhuman and distrurbing features of modern capitalism is its insistance upon making workers pretend like they enjoy their jobs.

Closer to home, there’s an easy way to see where this perspective on work comes from and how it plays out in practice: just look at Millennials. One need only look at the expansive body of business literature on “managing Millenials” to appreciate the challenge this generation is posing to traditional work norms. Gallup reports that only 29% of Millenials are “engaged, meaning they are emotionally and behaviorally connected to their job and their company.” And this has earned them the widespread reputation “of being lazy and not wanting to work”. But as Andrew Van Dam reports in his article on “the myth of the lazy Millennial,” that’s not what’s going on here:

Millennials entered the workforce amid two significant recessions and the jobless recoveries that followed, meaning they were always pitted against legions of laid-off, more-experienced workers…

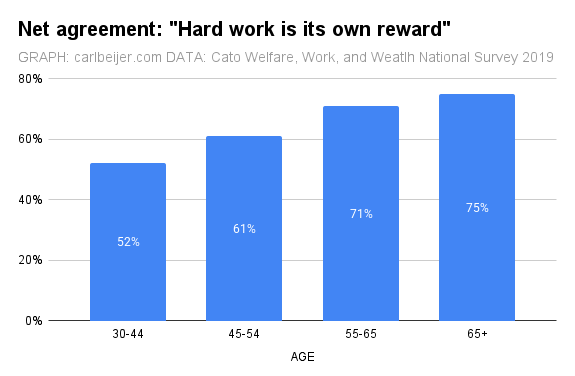

The result: an employment market where it’s hard to get hired and even harder to advance. And that’s why we see polls like this:

Again, just as a demonstrable fact, Millennials do not value work in the same way that older generations do. But this has nothing to do with them being lazy or incapable and everything to do with their economic conditions. Millennials have correctly learned that hard work is not rewarding because they have worked extremely hard and have not been rewarded for it.

Imagine if, instead of acknowledging these basic facts, we decided that it was extremely problematic to point out that Millennials don’t place the same value on work that later generations do. This wouldn’t just be incorrect — it would also be cruel and unfair because it would paint over one of the serious impacts our economy has had on Millennials. Being taught that no amount of effort is likely to improve your life very much is an extremely hard lesson to have to learn, particularly since capitalist culture always tells us the exact opposite.

This point, of course, also generally applies to the poor.1 Mason may think he is doing them a favor by pretending that they see things like “work” and “discipline” in the exact same way that the more fortunate see it, but this is both incorrect and insulting. It is actually to the credit of the poor that they often see through the myth of meritocratic capitalism much more clearly than the middle class does. It is a testament to their wisdom when they value things more than work discipline and their usefulness to employers. As Marx put it, for workers under capitalism, “labor does not belong to his essential being.” Or as Pope John Paul II put it more poetically: “Work is for man, not man for work”.

Mason may think he’s defending the poor, but I suspect there’s a better explanation. If you are a successful liberal-left academic, you almost certainly understand that meritocracy is a myth — at least, academically. But you will also be sorely tempted to see all of your success as earned by all of your hard work and discipline. This leaves you with a choice: either insist that people like the poor and Millennials are wrong not to care as much about work — or pretend that they secretly value it just as much as you do.

Thanks for reading! My blog is supported entirely by readers like you. To receive new posts and support my work, why not subscribe?

Refer enough friends to this site and you can read paywalled content for free!

And if you liked this post, why not share it?

In fact, it would be more accurate to say that this point only applies to the poor, some of whom happen to be Millennials.