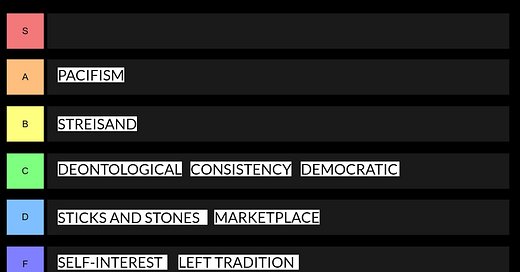

Ranking the arguments for free speech

Why are some of the most popular arguments for free speech so terrible?

Contemporary debates around free speech have become so cynical and imbecilic that one can plausibly point to them as an argument against it: this is what people want to defend? And one of the major reasons for this, I think, is that we rarely distinguish between the different arguments for free speech, much less acknowledge that some of them are stronge…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Carl Beijer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.