Quietism, wokeness, and the bewitchment of language

A powerful feature of human psychology has become a major obstacle to sane political debate.

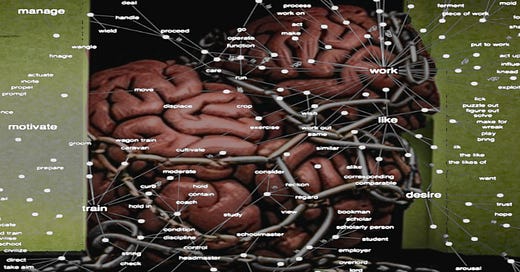

As a Quietist — someone who believes that a lot of our political and philosophical problems emerge, in part, from confusion about language — I’ve always been fascinated by the mind’s compulsion to imbue words with objective meaning. I don’t mean by this our ability to interpret the substantive meaning that language often conveys; I mean that when we enc…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Carl Beijer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.