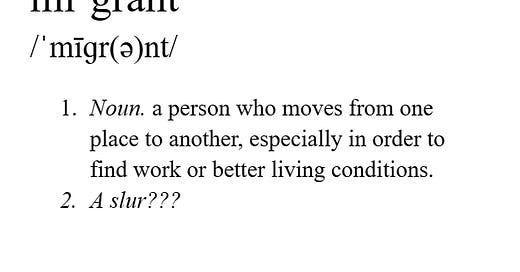

There’s a new slur on the horizon: “migrants.” Or at least that’s what I’m hearing from the familiar genre of busybody liberal whose politics mostly revolve around language policing. And though I have no doubt that we’ll soon be told that “migrant” has been a slur since time immemorial, the fact is that no one had a problem with it as recently as a few …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Carl Beijer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.