Major study overthrows the "Great Leveler" argument against socialism

Study suggests that governments - and not just violent upheavals - can reduce inequality.

The structure of a government can have enormous effects on economic inequality, a groundbreaking new paper published by the National Academy of Sciences concludes.

This point may seem obvious to socialists, but among archaeologists it has for decades come under increasing scrutiny. Decades of research seemed to indicate that inequality was very closely related to population size, culminating in Walter Scheidel’s 2017 book The Great Leveler. There, Scheidel argued that only four factors in human history had ever put a serious dent in inequality: total war, violent revolution, state collapse, and plagues. And even those shifts were only temporary. As he concluded in the book’s final chapter,

policymaking can only take us so far. Time and again the compression of material imbalances within societies was driven by violent forces either that were outside human control or that are now far beyond the scope of any viable political agenda…the prospects of future leveling are poor. (443)

Leveler, in my view, is one of the most serious critiques of the socialist project we have seen in the last century. It is an extraordinary work of material analysis, and since its argument is primarily empirical it is difficult for anyone outside the field to respond to it. I will freely admit that while I have written about Leveler several times in the past I have avoided this main argument simply because I’ve had no way to answer it. If we take it seriously, Leveler seems to delegitimize any political attempt to fight economic inequality — socialist, reformist, or otherwise.

That’s why this new paper is so important. In Assessing grand narratives of economic inequality across time, lead researcher Gary Feinman and his colleagues examined more than 50,000 archaeological finds over the past 10,000 years. This is a truly unprecedented effort; in contrast, Scheidel is forced to rely on an interdisciplinary hodgepodge of tax records, grain volumes, burial wealth displays, and so on. Feinman’s approach is unified and objective: he measures the relative sizes of houses in a given settlement or city as a measure of inequality. He then compares that measure to several other relevant quantitative measures of the society in question, an approach that produced several important findings:

Larger populations only expand the range of potential inequality towards greater concentrations of wealth;

Major cataclysms (such as the fall of Rome) expand the potential for greater equality;

States with significant natural resources and trade routes tend to be less equal than those with less;

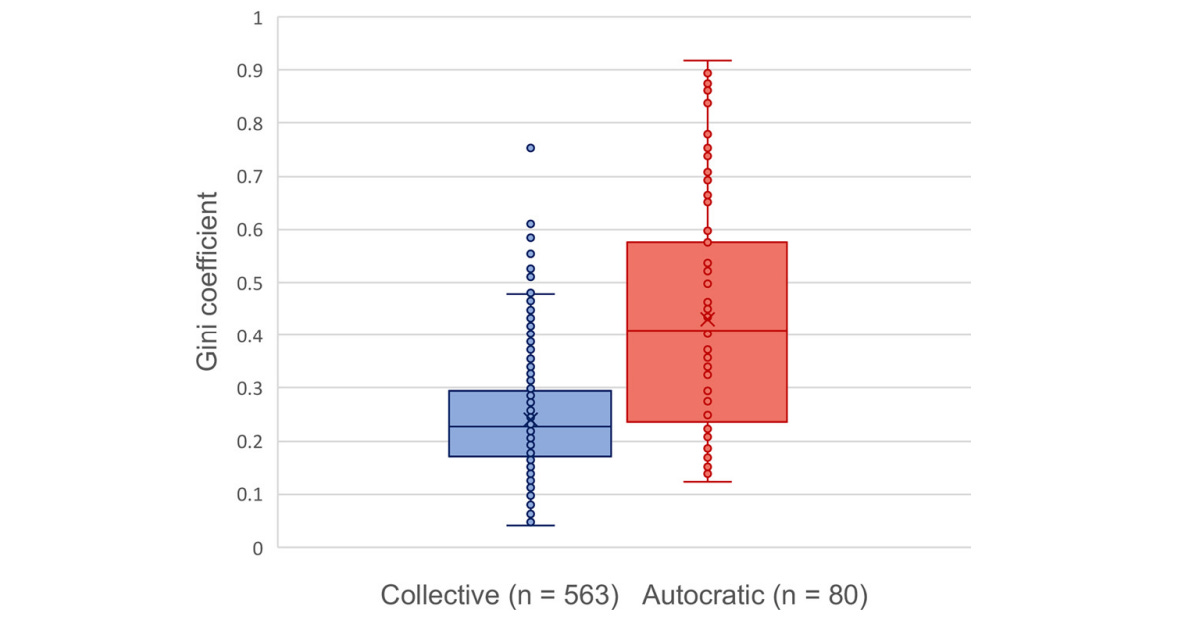

Democratically organized states can achieve greater equality than autocratically organized states, which can achieve much greater inequality; and

States with multileveled hierarchies have a greater potential for inequality than states with a smaller number of hierarchical levels.

The upshot of the study, then, is twofold. First, contrary to the theory that societies are generally growing more unequal over time, the authors find “that we have not uniformly moved from an equitable past to an unequal present.” Second, this data reveal patterns of inequality “that are neither uniform nor linear, but afford roles to human agency and institutions.”

The “Great Leveler” theory, in other words, simply isn’t supported by the data. Societies do not show a consistent tendency to become less equal, and violent upheavals aren’t the only things that can equalize society. In particular, if you can organize your state in a way that is relatively democratic and hierarchically minimalistic, you significantly reduce the potential for economic inequality. These are not offered as the only way you can reduce inequality, but they open the door for government design and intervention.

Socialists should be encouraged by the finding of a significant relationship between democracy and equality. The finding about hierarchical structure also has implications for government design that correspond with general leftist intuitions about flattening hierarchies, though the specifics are a bit less clear. Feinman’s paper, in any case, is an extraordinary piece of scholarship that rescues socialist politics from the suffocating pessimism of The Great Leveler. Let’s hope its findings hold up.

Thanks for reading! My blog is supported entirely by readers like you. To receive new posts and support my work, why not subscribe?

Refer enough friends to this site and you can read paywalled content for free!

And if you liked this post, why not share it?