Determinism in the USSR, Part 1: Introduction

Why did the Soviet Union become so invested in free will ideology?

For the next few weeks I’ll be posting a multi-part series on the history of philosophical determinism in the Soviet Union. This is part one.

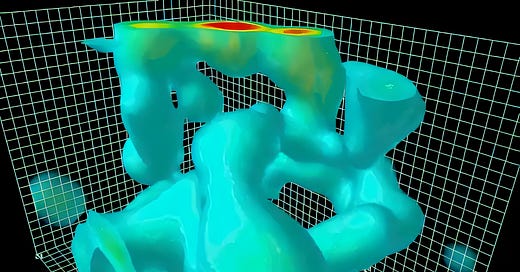

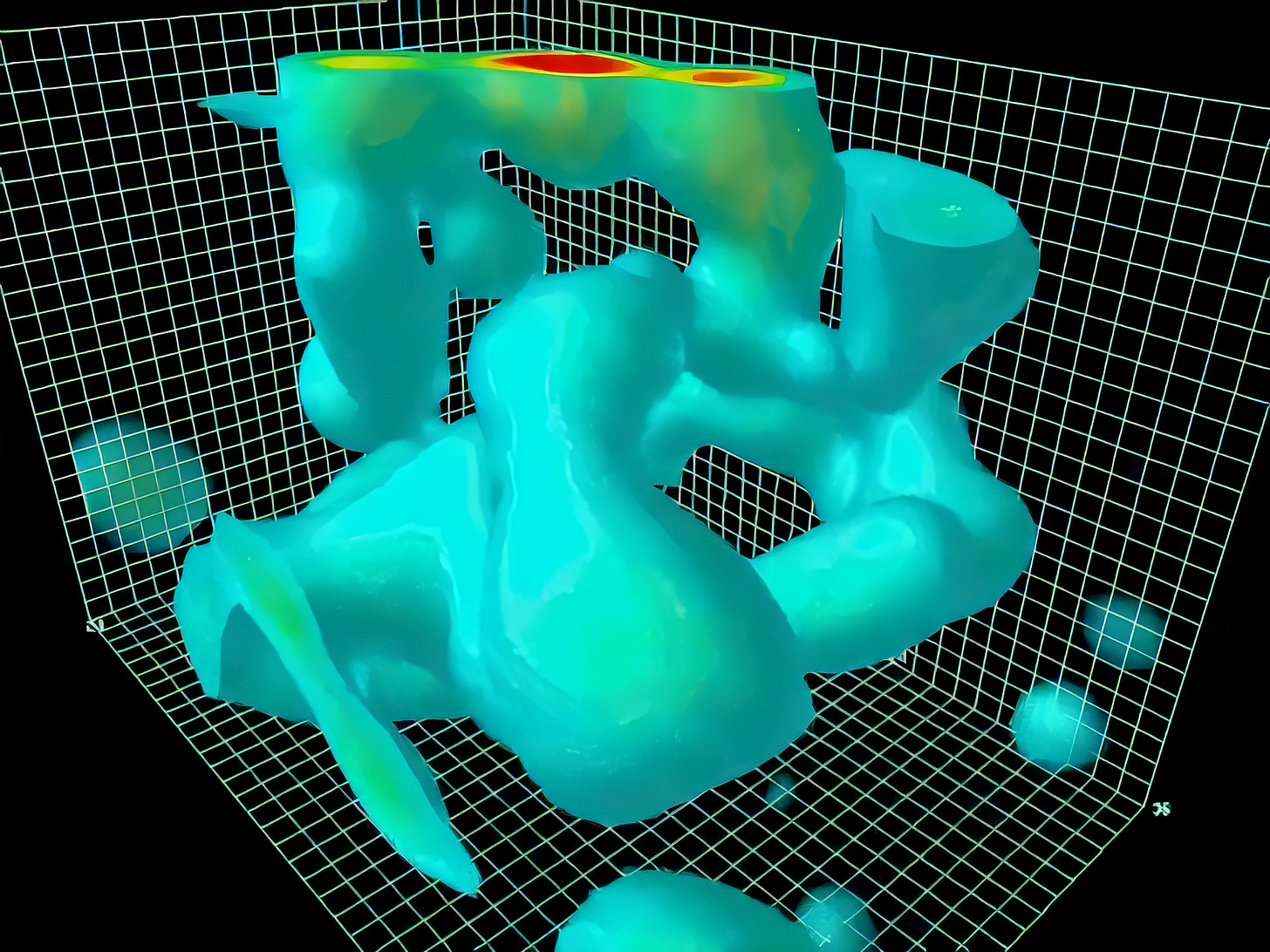

Ghost particles are a unique exception to the most powerful law in the universe: the law of physical cause-and-effect. As predicted by quantum physics, these tiny s…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Carl Beijer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.